In this Part

Determining whether your company can pay all its bills on time with liquidity metrics

Evaluating how well your company generates and manages profits with profitability metrics

Using debt analytics to measure how effective your company is at managing its debt

Staying debt healthy

Paying the Bills

Liquidity metrics measure a company’s ability to pay its bills. Companies use the equations in this category to measure their ability to pay for the costs of doing business with the assets they currently have available to them. Just as a person who writes a bad check to pay their water bill shouldn’t expect to use the toilet for much longer, a company that can’t pay its bills will have to stop output in the near future. This scenario doesn’t necessarily mean that the company is losing money; it just means the company has bills due before the money it has earned has been received.

By contrast, this category of ratios may indicate whether a company is holding on to too much cash, illustrating that the company isn’t utilizing the cash effectively to generate value.

When I discuss the variation of the values calculated in these metrics, I say things like “as the value increases” or “as the value goes high.” These calculations don’t have “perfect” or “correct” values. They can vary dramatically depending on the industry in which a corporation operates, or on the current macroeconomic conditions. So, terms like “too high” or “too low” are variable. They are best under- stood in the context of the industry and based on what the competitors are doing. . . at least until you know the corporation’s detailed financial needs.

Days sales in receivables

When a company sells a product and the person who bought it doesn’t pay right away, the money that the company will collect in the future is called a receivable. To calculate the number of days it takes for a company to finish collecting the money a customer owes it, the company can use the days sales in receivables metric, which looks like this:

To use this equation, follow these steps:

Find gross receivables in the asset section of the balance sheet and net sales near the top of the income statement.

Divide net sales by 365 (the number of days in the year). The number you get is the average amount of income after costs that the company is making per day in a given year.

Divide the gross receivables by the answer in Step 2 to get the number of days on average it took the company to collect a single receivable.

Because the company knows how many sales it made during a year and what percentage of those sales were receivables meant to be collected in the future, it can determine the average receivables per year. As the value of this ratio goes up, the company is taking longer to collect its money. If the value goes down, the company is collecting its money faster.

If this ratio is too low, it may indicate that the company could increase sales by extending credit to potential customers who currently don’t have the cash to purchase all at once. If this ratio is too high, it could indicate that the company could be generating more value if it more aggressively collected what it owed and then utilized that money.

Although any sale made on credit becomes a receivable, companies usually collect money for inexpensive products very quickly. Thus, this particular metric is meant more for companies that sell very expensive products that require multiple payments, like machinery or vehicles. These companies like to plan ahead so they don’t spend too much money making inventory before they collect on their existing sales.

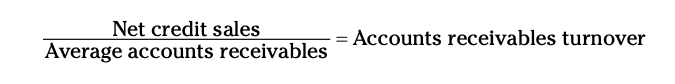

Accounts receivables turnover

Companies like to know that they’re collecting the money that customers owe them. To find out exactly how well a company is at making sales that will be collected in the future and how well the company is at collecting the money that people owe it, the company can use the accounts receivables turnover metric, which it calculates like this:

To use this equation, follow these steps:

Find net credit sales on the income statement.

Use the balance sheets of the current year and the previous year to calculate the average gross receivables: Add the accounts receivables from both years and divide that number by 2.

Divide net sales by the answer in Step 2 to get the accounts receivables turnover.

If this ratio is too high, it could indicate that the company is ineffective at collecting what is owed to it or that it has uncollectables reported as assets. If this ratio is too low, it may indicate that the company could increase sales by extending credit to potential customers that currently do not have the cash to purchase all at once.

This metric is called a turnover because it measures the number of times the average value of a company’s accounts receivables turns over — in other words, the number of times the accounts receivables are collected as sales and start fresh with brand new receivables. Of course, the company is still acquiring receivables,

so the receivables account is never depleted; however, the average value can still be collected as sales. If the number is very low, the company may be having a difficult time collecting the money it’s owed.

Accounts receivables turnover in days

As a company collects the money it’s owed, the total amount the company is owed on average goes up or down depending on how quickly it collects its money. As a result, companies like to know how many days it takes them to collect an amount equivalent to the average total amount they’re owed. They can calculate this number by using accounts receivables turnover in days, which looks like this:

Follow these steps to use this equation:

Use the balance sheets of the current year and the previous year to calculate the average gross receivables: Add the accounts receivables from both years and divide that number by 2.

Find net sales near the bottom of the income statement for the current year.

Divide net sales by 365. The answer you get is the average number of sales the company is making per day in the current year.

Divide the answer in Step 1 by the answer in Step 3 to get the number of days it takes to collect as sales a total value that is equivalent to the average amount of money the company is owed as receivables.

Whether too low or too high, this ratio indicates much the same thing as the other receivables ratios. This one is unique in that it gives an average count of days, which is useful for planning purposes.

Days sales in inventory

How long does it take for a company to turn its inventory into sales? You can answer this question by using the metric known as days sales in inventory:

To use this equation, follow these steps:

Find the ending inventory on the balance sheet at the end of the year (the value of the inventory listed at the end of the year is the ending inventory) and the cost of goods sold (COGS) in the revenue portion of the income statement (usually somewhere near the top).

Divide the cost of goods sold by 365.

Because cost of goods sold includes the costs of making a product without all the additional business costs (for example, it includes the materials to make the product but not the cost of janitorial), dividing this number by 365 tells you how much money a company is spending on average per day to make a product.

Divide the value of the ending inventory by the answer in Step 2 to determine how many days it takes a company to sell the total value of its inventory.

Of course, the company continues to make more inventory, but measuring the inventory at the end of the previous year gives you the number of sales you’re comparing the days sales in inventory to. A lower number means the company is selling its inventory faster, while a higher number means the company takes longer to sell its inventory. If this becomes too high, it may indicate that the company is producing too much and can’t sell it off. If this number is too low, it may mean that it is time to invest in expanded production (or increase prices).

Inventory turnover

The number of times a company’s inventory is sold and replenished is called the inventory turnover. Here, the term turnover means that the total value of a company’s inventory has been completely depleted and recovered. A high number means that the company cycles through its inventory very quickly. You calculate this magical value by using the following equation:

Follow these steps to use this metric:

Find the cost of goods sold in the revenue portion of the income statement.

Use the balance sheets from the current year and the previous year to find average inventory: Add the two inventory values (find them in the assets section) and divide the total by 2.

A very high ratio here may indicate difficulty keeping up with demand. A very low ratio may indicate difficulty selling existing inventory.

Inventory turnover in days

When a company makes a lot of a single product, it wants to have an idea of how long it will take to sell it all. Knowing this can help the company estimate how quickly it will make money to pay off its bills and how much money it should spend on making more inventory, so it doesn’t have too much inventory or, even worse, run out altogether. Believe it or not, selling something you don’t have is quite difficult, as is buying more supplies if you can’t sell what you’ve already made. To avoid both of these mistakes, companies use the inventory turnover in days metric.

Here’s how to use this equation:

Use the balance sheets from the current year and the previous year to find the average inventory: Add the two inventory values (find them in the assets section) and divide the total by 2.

Find the cost of goods sold in the revenue section of the income statement.

Divide the cost of goods sold by 365.

Divide the answer in Step 1 by the answer in Step 3 to get the inventory turnover in days.

Unusually high metrics here may indicate too much inventory, which can be an expensive problem because unsold inventories are expensive to store. Generally, companies should keep this number as low as possible, by using just-in-time (JIT) inventory management.

Operating cycle

The operating cycle is a big deal, so try to remember this one in particular. Have you ever walked into your favorite store and wondered how long it takes the company to do everything from start to finish? From purchasing supplies needed to make a product to the time it takes to sell that same product? No, like a sane person, you probably haven’t considered this, but the store’s management and investors certainly have.

The period of time from the moment a company purchases its inventory to the moment the final payment on the sale of that inventory is made is called the operating cycle. You figure out a company’s operating cycle by using this equation:

Accounts receivables turnover in days + Inventory turnover in days = Operating cycle

Both of the numbers that go into this equation come from metrics that I discussed earlier in this chapter. So, unfortunately, you need to do some preliminary calculations before you can figure out a company’s operating cycle. Trust me, it’s worth the extra work. After all, the end result is a number that tells you how well a company is managing its assets by calculating how long it takes the company to make money from start to finish. As with many of the other metrics in this chapter, you have to compare this value to other companies in the industry and against itself for it to be really useful. Aircraft carriers have longer operating cycles than bubblegum manufacturers, for instance. That means that corporations with longer operating cycles will tend to have higher liquidity needs.

If the operating cycle is unusually high, it may indicate some bottleneck in production or another issue that is slowing operations.

Working capital

If you paid off all your short-term debts, what would the value of your remaining short-term assets be? For example, if you paid off your credit cards, would you have any money left in your bank account? Companies care about this, too, and to measure it, they use the working capital metric, which tells them exactly what their net value is in the short run. Here’s what this metric looks like:

Current assets – Current liabilities = Working capital

To use this equation, follow these steps:

1. Find current assets and current liabilities on the balance sheet in the assets and liabilities sections (go figure!).

2. Subtract current liabilities from current assets to get the working capital.

If a company has more short-term assets than short-term liabilities, the com- pany’s working capital is a positive number. Companies like to see positive working capital because it indicates that they can pay off their debts for at least the next year or so. Negative working capital is a very dangerous position to maintain.

Current ratio

Another way to look at a company’s liquidity for the next 12 months is by using the current ratio. This ratio calculates the number of times a company could pay off its current liabilities, using its current assets. Here’s what the ratio looks like:

Current assets / Current ratio = Current liabilities

So, if a company had twice as many current assets as it had current liabilities, it has a current ratio equal to 2.0. If a company had half as many current assets as it had current liabilities, then its current ratio is 0.5. Because the current ratio includes inventories in addition to other forms of current assets, a low current ratio can indicate that a company is either at risk or very good at managing a low inventory (which is good for keeping costs down). In other words, you have to have some context to make this ratio really useful.

Acid test ratio (aka Quick Ratio)

Some companies that sell very large or expensive items have a difficult time selling inventories. To see whether these companies can pay off their debts due within the next year, you can use a metric called the acid test ratio. The acid test ratio uses all current assets except inventories and divides their value by the current liabilities, as you can see in the equation that follows:

Cash equivalents - Marketable securities + Accounts receivables / Current liabilities = Acid test ratio

Follow these steps to put this equation to work:

Find the equivalents, marketable securities, and accounts receivable in the assets portion of the balance sheet and the current liabilities in the liabilities portion.

Add together the company’s cash equivalents, marketable securities, and accounts receivables.

Divide the answer in Step 2 by the value of the current liabilities to get the acid test ratio.

This ratio shows how many times a company could pay off the debt that’s due within the next 12 months using current assets other than inventory. Because this value doesn’t include inventories, it’ll be smaller than the current ratio, but it’s still important to consider because it shows whether a company has enough cash and other assets to quickly turn into cash to pay off debts owed and avoid bankruptcy. Even so, a low acid test ratio may mean the company is at risk, or it may mean that the company is very effective at managing its accounts receivables by collecting them very quickly. The moral of the story: Be sure to interpret this ratio in the context of the company’s receivables management.

Cash ratio

The strictest test of a company’s liquidity is the cash ratio. This metric utilizes only the most liquid of assets — cash equivalents and marketable securities — to determine how many times a company could pay off its liabilities over the next 12 months. For companies that have very high accounts receivables, either because they sell expensive items that customers make long-term payments on or because they issue a lot of bad debt, this is often the best ratio to use. Here’s how to calculate it:

To use this equation, follow these steps:

Find the cash equivalents and marketable securities in the assets portion of the balance sheet and the current liabilities in the liabilities portion.

Add together cash equivalents and marketable securities.

Divide the answer in Step 2 by current liabilities.

This is the equivalent of feeling comfortable paying your bills using the money you currently have in your bank account. It’s a good feeling to know that you don’t have to worry about selling anything or relying on expected future income to pay the bills. However, having a ton of cash in the bank also means you’re not investing it very effectively.

Sales to working capital

The appropriate level of liquidity varies depending on the individual company in question, but you can use the sales-to-working capital ratio metric to help determine whether a company has too many or too few current assets compared to its current liabilities. This metric looks like this:

Sales to working capital Working capital

Here’s how to use this equation:

Find sales at the top of the income statement.

Calculate working capital by subtracting current liabilities from current assets (both of which you find on the balance sheet).

Divide the value of the company’s sales by its working capital to get the sales to working capital.

A very high number may indicate that a company doesn’t keep enough current assets available to maintain inventory levels for the number of sales it’s making. A very low number may mean that the company is keeping such a high proportion of its assets current that it isn’t using its assets to generate sales. Watching how a company’s sales to working capital vary over time compared to that of its competitors can help give context to the other liquidity metrics by measuring how effectively the company is managing its working capital.

Operating cash flows to current maturities

The ratio of operating cash flows to current maturities utilizes the cash flows a company generates from its operations to determine its ability to pay any debts that are maturing within the next year. This ratio is different from the other liquidity metrics in this section in two important ways:

ether a company can pay debts by using the cash flows it than the assets it has on hand.

» It measures the company’s ability to pay off any liabilities that are going to be due within the next 12 months rather than just current liabilities.

In a way, this ratio determines a company’s ability to keep its cash flows liquid rather than its assets. You measure it like this:

Operating cash flows

Current maturities of long-term debt and notes payable

Operating cash flows to current maturities

Follow these steps to use this equation:

Find operating cash flows in the statement of cash flows and long-term debt and notes payable in the liabilities portion of the balance sheet.

Add together the long-term debts and notes payable that are going to mature in the next 12 months.

Divide operating cash flows by the answer in Step 2 to get operating cash flows to current maturities.

As with the other liquidity metrics, the goal of this calculation is to determine whether a company can pay off the debts that are due within a year. A higher ratio indicates that the company is at low risk of defaulting on its debts, while a low ratio may mean that the company is at risk of defaulting. Operating cash flows aren’t as dependent on asset management as either receivables or inventories, so this metric can be more dependable, particularly for those investors who are considering providing the company with a loan or purchasing its bonds.

Working Your Assets

The primary purpose of a company is to generate profits. Of course, companies can’t just charge any price they want and make tons of profits. If a company charges too much, customers will go to the competition, so every company is limited in its profitability. The following metrics are all ways to measure how well a company generates profits, as well as how effectively it is at managing them.

Net profit margin

The most common measure of a company’s profitability is the net profit margin. This metric measures the percentage difference between net income and net sales. In other words, it measures the percentage of a company’s sales revenues that don’t go toward business costs. You measure profit margin like this:

Net income 100 Net profit margin Net sales

Here’s how to use this equation:

Find net income near the bottom and net sales near the top of the income statement.

Multiply net income by 100. You use the number 100 here to form an answer that’s a percentage rather than a decimal number.

Divide the answer in Step 2 by net sales to get the net profit margin as a percentage.

The net profit margin tells you what percentage of the total money made by a company increases the value of the company or its owners rather than being spent on costs. However, a low-profit margin doesn’t necessarily mean low profits. A company with a 1 percent profit margin makes less money on every sale than a company with a 2 percent profit margin, but the company with a 1 percent profit margin may make up the difference with a greater volume of sales.

Note: Some authorities say to divide net income by net sales and then multiply the answer by 100. Don’t worry, my preceding equation gives you the same answer. Test it for yourself or go ask your math teacher.

Total asset turnover

A company may have a lot of assets, but just how effective is it at using those assets to generate sales? To find out, you use a ratio called total asset turnover, which you calculate like this:

Net sales Total asset turnover Average total assets

Follow these steps to use this equation:

Find net sales at the top of the income statement.

Use the balance sheets from the current year and the previous year to find the average total assets: Add together the total assets of the current year and the total assets of the previous year, and then divide that value by 2.

Divide net sales by average total assets to get the total asset turnover.

Assets that don’t generate sales simply cost money. The simplest example here is inventory: If a company has assets in the form of inventory that isn’t being sold, then it’s paying for the storage of that inventory without actually generating sales on it. The total asset turnover metric helps indicate how well a company manages its assets.

Return on assets

A company may have a lot of assets, but how effective is that company at using its assets to generate income? To find out, use a ratio called return on assets, which you calculate like this:

Net income - Return on assets Average total assets

Use this equation by following these steps:

Find net income near the bottom of the income statement.

Use the balance sheets from the current year and the previous year to find the average total assets: Add together the total assets of the current year and the total assets of the previous year, and then divide that value by 2.

Divide net income by average total assets to get the return on assets.

The primary difference between return on assets and total asset turnover is that return on assets measures a company’s ability to turn assets into income rather than just sales. In other words, return on assets helps determine whether a company can use its assets to develop profitability, not just a volume of sales.

Operating income margin

The operating income margin measures the percentage difference between operating income and net sales. This metric differs from net profit margin in that it concerns itself only with income from operations, excluding a number of costs and revenues that go into measuring net income. You measure operating income margin with this equation:

Operating income Net sales

Operating income margin

To use this metric, follow these steps:

Find net sales at the top of the income statement.

Find average operating assets by using the balance sheets from the current year and the previous year: Add together the operating assets of the current year and the operating assets of the previous year and divide that value by 2.

Divide net sales by average operating assets to get the operating asset turnover.

You may prefer to measure operating income margin rather than net income margin because it’s more strictly reflective of how profitable a company’s operations are and how competitive a company is in its primary purpose.

Operating asset turnover

How effectively is a company using its operating assets to generate sales? To find out, use a ratio called operating asset turnover, which you calculate like this:

Net sales Operating asset turnover Average operating assets

Follow these steps to use this equation:

Find net sales near the top of the income statement.

Find the operating income on the income statement if it’s listed; if it isn’t, calculate it by subtracting operating expenses and depreciation from the company’s gross income.

Divide the operating income by net sales to get the operating income margin.

This metric determines how well a company is using those assets used specifi- cally in the company’s primary operations to generate sales. Operating asset turnover is different from total asset turnover in that it doesn’t take into consid- eration all assets and it may be more reflective of the company’s competitiveness in its primary operations.

Return on operating assets

How effectively does a company use its operating assets to generate income? Use the return on operating assets to find out:

Operating income Return on operating assets Average operating assets

To use this metric, work through these steps:

Use the income statement to find the operating income: Subtract operating expenses and depreciation from the company’s gross income.

Use both the current year’s balance sheet and the previous year’s balance sheet to find the average operating assets: Add together the operating assets of the current year and the previous year and divide that value by 2.

Divide operating income by average operating assets to get the return on operating assets.

The primary difference between return on operating assets and operating asset turnover is that return on operating assets measures a company’s ability to turn operating assets into income rather than just sales. In other words, return on operating assets determines whether a company is using its operating assets to develop profitability rather than just a volume of sales. Like other measures of operating assets, this one differs from return on assets in that it focuses on the company’s core operations instead of giving an overall picture.

Return on total equity

Imagine that you own equity in a company. You’d probably want to know how much value the company is making for you, the stockholder. The good news is you can calculate the amount of income a company can generate with the equity you have invested in it by using the return on total equity metric, which looks like this:

Net income after tax Average total equity

Return on total equity

To put this equation to work for you, follow these steps:

Find net income after tax near the bottom of the income statement.

Find the average total equity by using the balance sheets from the current year and the previous year: Add the total equity from the current year and the previous year, and then divide the sum by 2.

Divide the current year’s net income after tax by the average total equity to find the return on total equity.

Regardless of whether a company has only common shares or also has preferred shares, this ratio takes all equity into account. So, if you’re a preferred shareholder, this is the return on equity you want to be concerned about.

Return on common equity

Return on common shares determines how much income a company can generate based only on the value of its common stock, discounting all other forms of equity. If a company issues only common stock and no other types, this metric will produce exactly the same number as the return on total equity. Here’s what the return on common equity looks like:

Net income after tax Average common equity

Return on common equity

To use this metric, follow these steps:

Find net income after tax near the bottom of the income statement.

Find average common equity by using the balance sheets from the current year and the previous year: Add the common equities from the current year and the previous year, and then divide the sum by 2.

Divide the current year’s net income after tax by the average common equity to find the return on common equity.

Return on common shares is an important ratio for any stockholder to know because it shows how well a company is performing in regard to the interests of those who hold equity.

DuPont equation

In the 1920s, someone at the DuPont Corporation decided to take a closer look at the return on equity by breaking it into its component pieces. Using the DuPont method, the return on equity looks like this:

Profit margin × Asset turnover × Equity multiplier = DuPont equation (or return on equity)

The equity multiplier is a debt management ratio that I discuss in Chapter 8. You don’t have to be familiar with it to understand how the DuPont equation works or how you can use it, but you can flip to the section “Equity multiplier” in Chapter 8 for more details.

If you break down the components in the preceding equation into their respective ratios, the DuPont equation looks like this:

Net income Net sales Assets DuPont equation (expanded) Net sales Assets Equity

Because net sales appear on top in profit margin and on the bottom in asset turnover, you can cancel it out. The same goes for assets, which you find in both asset turnover and equity multiplier. That leaves you with only net income and equity:

Net income Equity

Notice that this simplified version of the DuPont equation is the same as the formula for return on equity (see the section “Return on total equity” for details). Why not just use the basic return on equity equation? The full analysis, as you see it in the expanded DuPont equation, provides a full explanation of the factors that

influence return on equity to determine exactly how a company could improve its profitability in this respect. A decrease in net sales, for example, increases profit margin but makes asset management less efficient. If the company can reduce the amount of assets on hand without harming the business, though, the profit margin will increase and the asset efficiency will improve, increasing the value of the company’s equity. Hence, using the DuPont equation can help a company to better manage its profitability.